Five Months On, What Scientists Now Know About The Coronavirus

Coronaviruses have been causing problems for humanity for a long time. Several versions are known to trigger common colds and more recently two types have set off outbreaks of deadly illnesses: severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (Mers).

Medical researchers have been studying everything we know about Covid-19. What have they learned – and is it enough to halt the pandemic?

But their impact has been mild compared with the global havoc unleashed by the coronavirus that is causing the Covid-19 pandemic. In only a few months it has triggered lockdowns in dozens of nations, and the disease continues to spread.

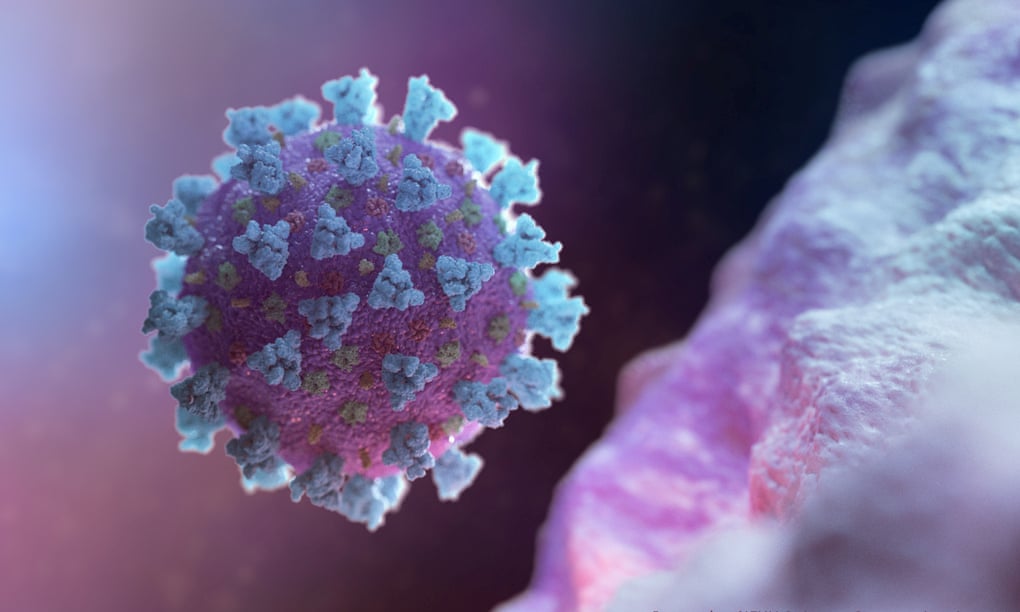

That is an extraordinary achievement for a spiky ball of genetic material coated in fatty chemicals called lipids, and which measures 80 billionths of a metre in diameter. Humanity has been brought low by a very humble assailant.

On the other hand, our knowledge about the Sars-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, is also remarkable. This was an organism unknown to science five months ago. Today it is the subject of study on an unprecedented scale. Vaccines projects proliferate, antiviral drug trials have been launched and new diagnostic tests are appearing.

The questions are therefore straightforward: what have we learned over the past five months and how might that knowledge put an end to this pandemic?

.png)

Where did it come from and how did it first infect humans?

The Sars-CoV-2 virus almost certainly originated in bats, which have evolved fierce immune responses to viruses, researchers have discovered. These defences drive viruses to replicate faster so that they can get past bats’ immune defences. In turn, that transforms the bat into a reservoir of rapidly reproducing and highly transmissible viruses. Then when these bat viruses move into other mammals, creatures that lack a fast-response immune system, the viruses quickly spread into their new hosts. Most evidence suggests that Sars-CoV-2 started infecting humans via an intermediary species, such as pangolins.

“This virus probably jumped from a bat into another animal, and that other animal was probably near a human, maybe in a market,” says the virologist Prof Edward Holmes of Sydney University. “And so if that wildlife animal has a virus it’s picked up from a bat and we’re interacting with it, there’s a good chance that the virus will then spread to the person handling the animal. Then that person will go home and spread it to someone else and we have an outbreak.”

As to the transmission of Sars-CoV-2, that occurs when droplets of water containing the virus are expelled by an infected person in a cough or sneeze.

.jpg)

How does the virus spread and how does it affect people?

Virus-ridden particles are inhaled by others and come into contact with cells lining the throat and larynx. These cells have large numbers of receptors – known as Ace-2 receptors – on their surfaces. (Cell receptors play a key role in passing chemicals into cells and in triggering signals between cells.) “This virus has a surface protein that is primed to lock on that receptor and slip its RNA into the cell,” says the virologist Prof Jonathan Ball of Nottingham University.

Once inside, that RNA inserts itself into the cell’s own replication machinery and makes multiple copies of the virus. These burst out of the cell, and the infection spreads. Antibodies generated by the body’s immune system eventually target the virus and in most cases halt its progress.

“A Covid-19 infection is generally mild, and that really is the secret of the virus’s success,” adds Ball. “Many people don’t even notice they have got an infection and so go around their work, homes and supermarkets infecting others.”

By contrast, Sars – which is also caused by a coronavirus – makes patients much sicker and kills about one in 10 of those infected. In most cases, these patients are hospitalised and that stops them infecting others – by cutting the transmission chain. Milder Covid-19 avoids that issue.