Behaviour Change Communication (BCC) refers to the strategic use of communications to encourage individuals and communities to adopt healthier and more sustainable practices. BCC has been successfully deployed to change behavioural practices, especially in the WASH space. (

Dreibelbis et al., 2013)

The approach uses a critical discernment of people’s behaviour and then aligns it with persuasive communication methodologies. Effective BCC requires, on the one hand, a strong knowledge of how individuals and communities think and act and, on the other, the customisation of messages and communication activities based on those observed needs and local realities….. Behaviour change does not happen overnight, it requires sustained efforts by multiple stakeholders working at different levels. ( BEHAVIOUR CHANGE COMMUNICATION, Tool – C5.02, IWRM Action Hub)

The above two viewpoints encapsulate the essence and challenge that behaviour change practitioners face when trying to ensure that communities adopt new and better methods to manage the benefits that are provided to them by the government.

To ensure that BCC programs are successful, the government has also designated a certain sum of money. For Swachh Bharat, for instance, the guidelines clearly state that up to 5 per cent of the total funding for programmatic components of SBM (G) Phase-II funds can be used for IEC and capacity building; up to 2 per cent can be used at the Centre level; and up to 3 per cent to be used at the State/district level towards educating communities in this regard but sadly this activity remains largely on paper or only sub-optimally implemented. This is where the corporates and their NGO partners come in.

Through defined training programs they can work with the village communities at different levels to make them understand and adopt better techniques and thinking for their own benefit.

Since independence, corporates have been supporting the communities that live around their factories with infrastructure and other benefits. Examples such as Tatanagar in Jamshedpur or Birlagram in Nagda have become famous as examples of successful public-private partnerships thriving over decades. Taking their example, many other domestic corporate houses over the last few decades have adopted the communities that were part of the geographic area where they operated and supported them with infrastructure and other benefits. The key to their success is their approach of inclusivity where all decisions are taken jointly by the corporates and village communities..

These success stories however are not prevalent all across India. The Lighthouse initiative launched earlier this year by the Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation (DDWS), Government of India in partnership with India Sanitation Coalition, to provide Solid and Liquid Waste Management (SLWM) facilities across all the villages of India, has as one of its KPIs, the need for effective IEC/BCC to achieve long-term impact and sustainability.

As part of the initiative, the government has agreed that while all infrastructure required by village communities to keep their surroundings clean and hygienic would be provided by them, the ongoing upkeep and maintenance of the infrastructure should be the responsibility of the community themselves. This is where the corporates are stepping in to provide support through BCC programs, educate the villagers on the benefits and need for usage of the infrastructure provided, and most importantly, to manage and maintain that infrastructure themselves in the long-term.

BCC is a critical component of successful WASH projects and I would say the most challenging and difficult to implement. When a toilet is built in a home, it makes the recipient happy to own something which gives them prestige in their community, however, using it and getting the other members of their families to use it is the most challenging part. Years of taboos defined through what is considered clean and unclean, respect of family elders, place of women in society, etc. continue to influence thinking in rural India and breaking these old and set patterns or norms very often requires years of hard and committed work.

Here lies the crux then of our collective challenge. While the government has hit upon a novel way in which they can make this happen by engaging in PPPs with Corporates which are physically part of these communities given the location of their factories and rural offices, this is not possible across all of rural India.

Developmental agencies like Tata Trusts, UNICEF, AKF and others have over several decades dedicated themselves to working with the most marginalised communities, providing them with infrastructure where none is available and educating them on the benefits of usage. Where possible, they work with the local governments to unlock government-related funding under schemes which are relevant to these communities.

But even with the collective help of the Corporates and Developmental agencies, this challenge of managing BCC over an extended period of time will not be met for all of India. For this to happen, only the government has the reach and financial depth to undertake the task.

One recommendation could be to strategically map each State into 3 broad zones, one, where Corporates are present and could support the activity, second, where the Development agencies are willing to step in and provide long-term BCC support, and the balance areas, where the government would have to step in themselves to provide the support to the communities.

But even this is not as simple as it seems. The age-old adage “you can take the horse to the water, but you cannot make the horse drink” applies here as well. Man is a creature of habit and if the habit is not something that bothers him physically, costs him financially or is in any way detrimental to his overall well-being, he finds it difficult to change his age-old habits. Open Defecation unfortunately falls into this category.

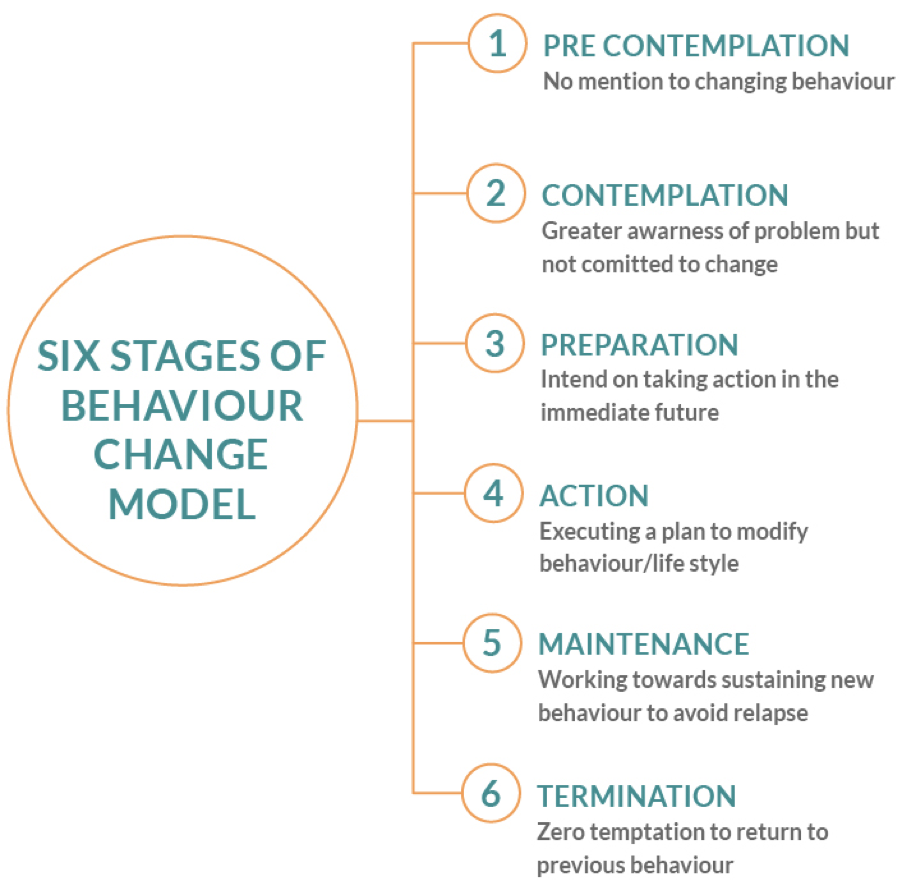

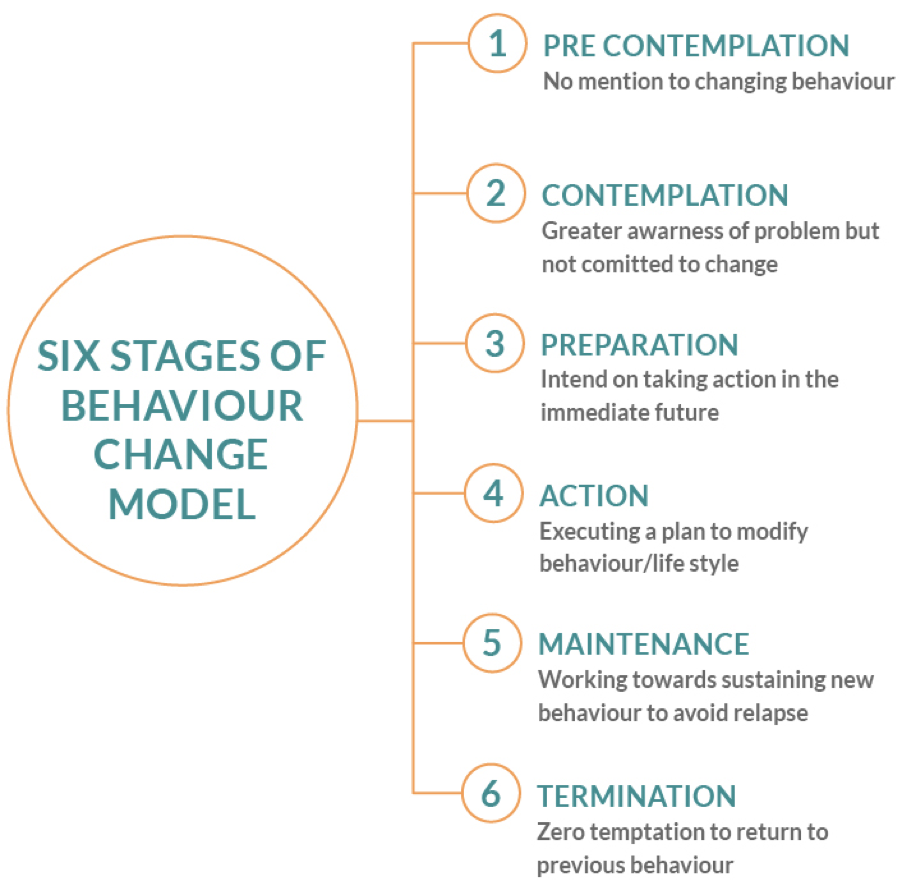

While it is true that OD is easier for men than women, many women groups actually welcome OD as they say it is the only time they can get outside their homes to be with their friends and exchange stories. Covid ironically was a great enabler of behaviour change. On the Transtheoretical Model of Health Behaviour Change chart ( Refer Appendix), it moved communities and people straight from stage 1 to stage 4 – Pre contemplation where the individual is still trying to understand whether a problem exists to making decisive action towards changing one’s behaviour. However, these types of events are not to be wished for or even contemplated.

How do we design long-term BCC and make it sustainable especially in sectors like WASH where it is critical for the long-term health and survival of the communities where it is being implemented?

Some of the challenges faced by BCC implementers relate to vested political interests, caste differences, religious motivations, educational limitations and a naïve belief in what is not broken does not need mending. Historically, political and caste differences polarised communities with the haves usually being the ones that were financially privileged and have nots watched from afar.

The involvement of village elders as long-term influencers, a clear definition of the household economies that can be achieved through maintaining a clean and hygienic environment, and constant reinforcement of the same messages over a period of time may be the only solutions for now aimed at successful, long-term BCC campaigns.

Equally important is the fact that the challenges we are trying to address under SMB 2.0 are next-gen sanitation issues which need equal focus on social, economic, political, and environmental dimensions. While Corporates and Developmental Agencies will continue to do their bit in striving to ensure that the communities they serve are made aware, slippages to unsafe practices are always a possibility and for this to be addressed the government has a major role to play in ensuring a better use of the IEC funds they allocate to states.

Setting up regular a review mechanism at a district level involving the private sector partners and seeking constant feedback from independent stakeholders on the level of acceptance of health and hygiene standards across the states and using their feedback to calibrate the manner in which developmental schemes are designed are some of the recommendations that could be considered on priority by the government, or else all the good work of the last few years may not sustain in the years to come.

Appendix

The Transtheoretical Model of Health Behaviour Change suggests that there are six stages of changing ones behaviour (

Prochaska and Velicer, 1997) (Figure 1):

-

Pre-Contemplation: At this stage the individual is yet to determine a problem even exists in their behaviour.

-

Contemplation: Acknowledgment of the problem begins, but the individual may not be ready to make a change.

-

Preparation/Determination: Getting ready to make a change.

-

Action/Willpower: Making decisive action towards changing behaviour. At this point the individual is undergoing increased awareness, education, and capacity building.

-

Maintenance: Here the individual tries to consistently maintain the changed behaviour. In this regard, consistency can be linked to a cycle of information and engagement to create an environment that is conducive towards positive change.

-

Termination: Full change occurs at this stage, the induvial does not return to old behaviour. Monitoring and evaluation is critical once this stage is reached to determine how effective was the change. “Slippage” or “relapse” may happen as certain individuals may return to old behaviours, especially if a conducive environment for change is not maintained.

Figure 1. Transtheoretical Model Stages of Behaviour Change (Adapted from Prochaska and Diclemente,1997)

PROCESS OF DESIGNING AND IMPLEMENTING BCC Here are the 6 steps for developing an impactful BCC programme strategy:

-

Enabler and Barrier Assessment: The first step to a successful BCC programme strategy is to carry out research about the target audience, including an extensive assessment of the behaviour to be changed and the reasons underpinning it. This requires assessing their knowledge, attitudes, needs, and habits (where do they seek information? On what platforms are they engaged? etc.). Barrier and enabler analyses can be supported by participatory methods such as community mapping and focus group discussions (Thomas, 2010). Practitioners are then able to identify the critical bottlenecks to be addressed, e.g. physical, attitudes, or institutional etc.(WaterAid, 2015). The Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, Behaviour (COM-B) Model is one methodology that is available and highlights the barriers for each area. The COM-B Model provides sample questions the practitioner should ask in identifying barriers for each area (Government Communication Service, 2021). The “Doer/Non-Doer” practical analysis framework developed by Bonnie (2013) focuses the enablers which have supported the early-adopters the desired behaviour change.

-

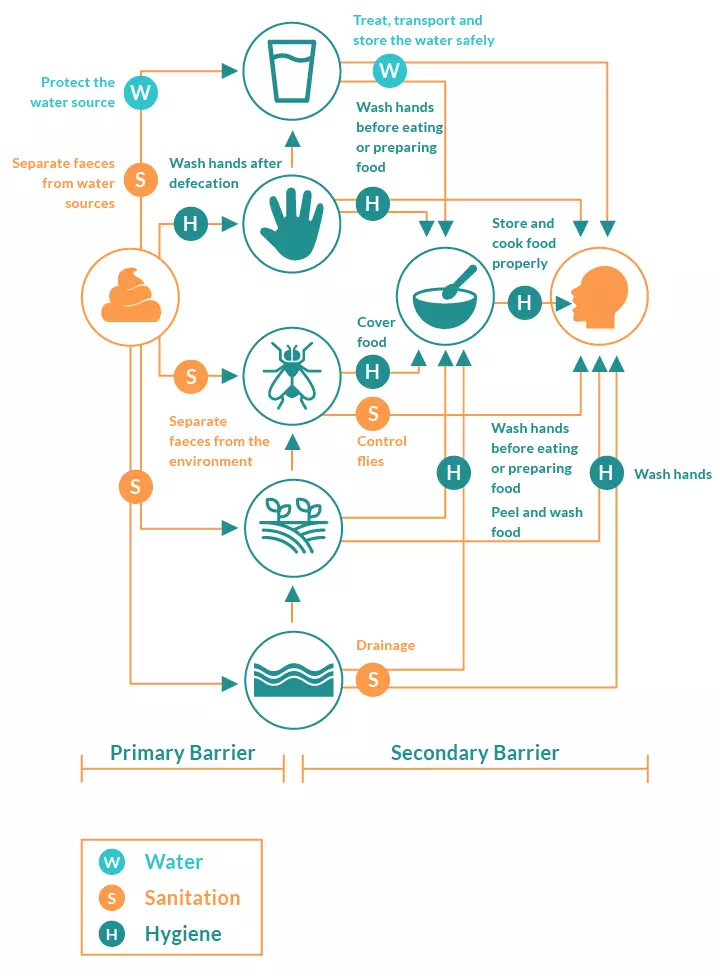

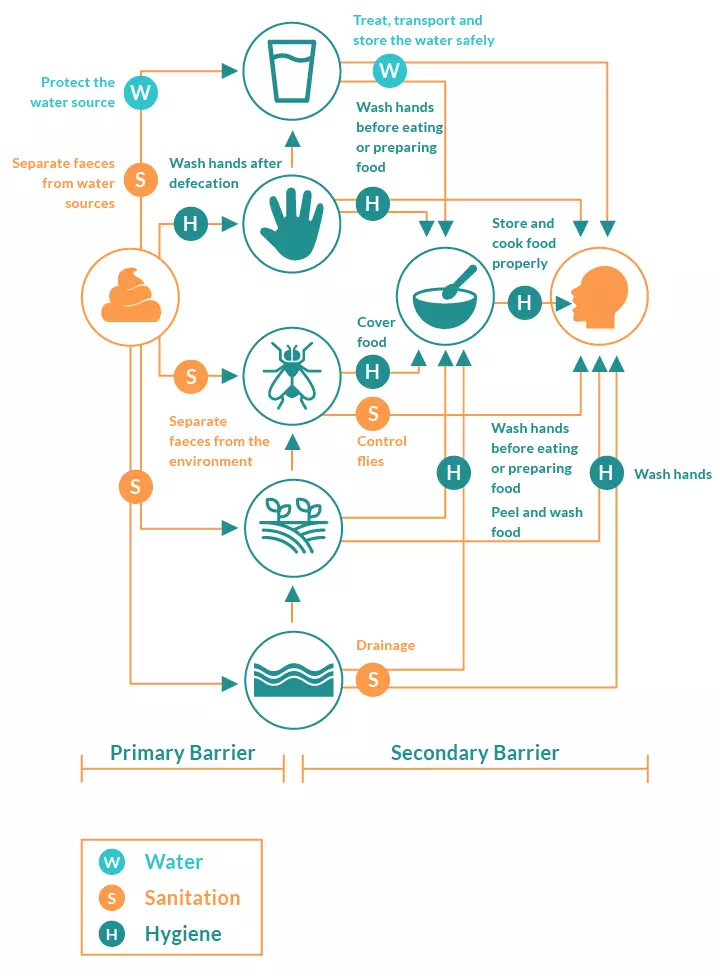

Developing and Building BCC Materials and Campaign: This is the stage where the designers of the BCC programme decide the message and the communication channel for engagement and interaction with the specific target groups. The messages need to be adapted to the target audience, to their level of knowledge, their challenges, and their perceptions about what can and cannot be done. The messages should be concise, easy to understand, and delivered in a manner that directly applies to them and their behaviour. The F-Diagram is one of the most commonly used BCC materials used in the WASH sub-sector (Figure 2). It is a graphic illustration that describes the potential faecal oral communications pathways which is intended to encourage people to adopt the safe sanitation and hand washing behaviours.

Figure 2. F-Diagram (Adapted from WEDC, 2013)

-

Pretesting: Once the BCC materials and the messages are prepared, pre-testing should be done for its effectiveness and motivation for change. To do so, conduct design workshops or focus groups involving key stakeholders, field workers, and members of the intended audience to also determine the best outlet for dissemination (i.e., print, radio, social media etc.) Then conduct a survey to determine if the produced materials meet the objectives of the programme, the needs of the audience, the message is clear and easy to remember and socially and culturally appropriate (SNV, 2016).

-

Implementation and Messaging: Implementation involves the distribution of created and tested content and messages, implementing the activities that reflect the new behaviour change (e.g., not dumping waste in rivers, hand washing with water and soap after defecations, using household water treatment) and training and capacity building of key players with the necessary skills for creating a multiplier effect for the desired behaviour change. Practical exercises and serious games can help carry out the messaging in a fun, interactive, and effective manner. Great examples have been developed for encouraging handwashing with soap (UNICEF, 2013) and safe menstrual hygiene management (WSSCC, 2016).

-

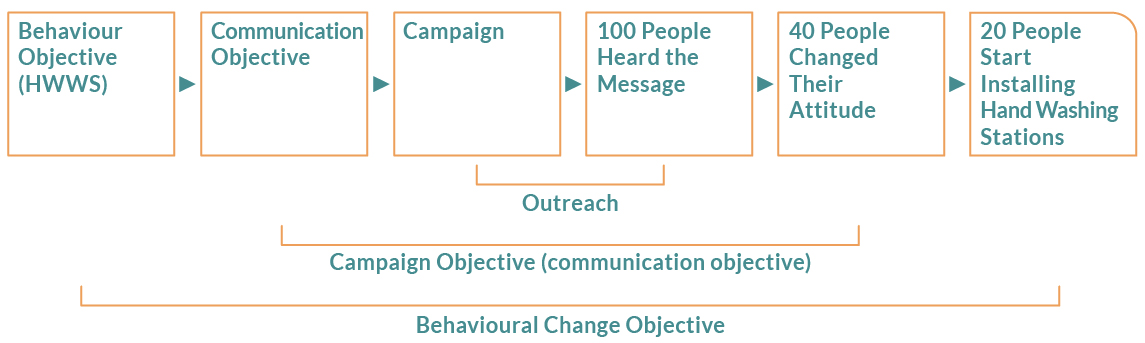

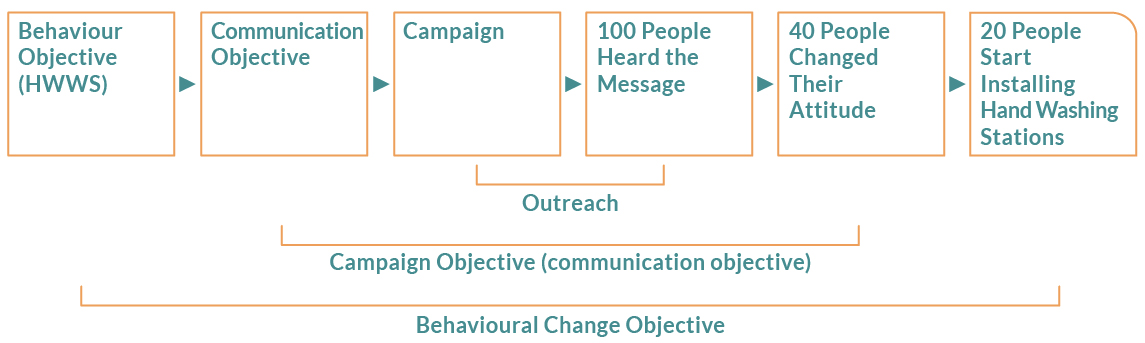

Monitoring and Evaluation: Refers to the tracking of existing statistics related to the targeted behaviour, tracking outputs to ensure that materials are utilised as planned with desired effects, and tracking the reaction of the target audience to ensure that they are motivated by the materials to change their behaviour (e.g., levels of pollution in rivers over time, % of people reporting washing their hands with water and soap after defecations, and % of households with residual chlorine in their drinking water). Evaluation of the monitoring results will also help identify the lessons learned, where the programme is weak and needs revision, and where it is strong and should be replicated. Feedback from the target groups and stakeholders are absolute necessities as based on these feedbacks, new sets of knowledge can be incorporated into the participant’s lives thus laying the foundation for new sets of behaviour. Additionally, when measuring effectiveness, BCC specialists must make a distinction between three levels; change in behaviour, the communication objective, and the outreach objective (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Areas for Consideration when Assessing Effectiveness (Adapted from SNV, 2016)

KEY BCC ASPECTS TO KEEP IN MIND

A successful BCC programme campaign requires extensive participation of the target population and stakeholders in all its stages of development and implementation, especially in the designing stage. The support of the government, health agencies, law enforcement, community leaders and active participation of the target participants is key to running a successful BCC campaign. This support is especially vital for the promotion and sustenance of new behaviour as an individual gradually contemplates, prepares, acts and maintains the newly acquired behaviour. This gradual change is not fixed as the individuals may relapse at any stage, thus calling for constant support. An individual needs a supportive environment for maintaining and sustaining positive changes. This can be done by reducing environmental conditions that support negative behaviours and increasing the conditions that support positive or desired results. Finally, behaviour change studies and programmes cannot be done at the surface level and therefore need to be well resourced (SHARE, 2018).

Blog writer: Natasha Patel, CEO, India Sanitation Coalition